by Lee Weinstein

It is generally conceded that H.P. Lovecraft’s major contribution to the genre of horror fiction was his replacement of the supernatural rationale in such stories with a scientific one. Fritz Leiber called Lovecraft “a literary Copernicus” in his essay of that title* because he created supernatural dread using “the terrifyingly vast and mysterious universe revealed by the swiftly developing sciences.” Leiber adds that “W.H. Hodgson, Poe, Fitz-James O’Brien, and Wells had glimpses of that possibility and used it in a few of their tales. But the main and systematic achievement was Lovecraft’s.”

In so saying, Leiber lightly casts aside the work of William Hope Hodgson, who, in his brief 13 year writing career, consistently and systematically used the mechanistic universe as a basis for the elements of terror in his fiction. He even went so far as to create a loosely constructed mythos, complete with a volume of ancient lore called the Sigsand Manuscript.

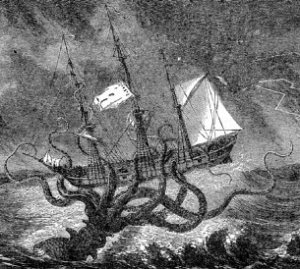

His second published story, “A Tropical Horror” (1905) is an early indication of the direction his fiction was to take. It consists largely of a first person account of the sole survivor of a ship attacked by a sea serpent. But it is not an adventure story of man against monster. Hodgson slowly builds up a mood of horror of the unknown. The creature is seen first a night. The narrator barricades himself in a steel-built halfdeck and listens in the darkness to the sounds of the creature and the screams of the men as they are eaten. As time drags on he gets occasional glimpses of the thing through a porthole. Finally, he is attacked through the porthole by a clawed tentacle, and a vast white tongue beset with teeth. The mood and structure of this story are appropriate to a story of supernatural horror, although the use of a non-existant sea creature makes it a legitimate science fiction story.

“From the Tideless Sea” (1906) and its sequel “More News from the Homebird” (1907) follow closely in the tradition of “A Tropical Horror,” creating an even greater atmosphere of supernatural horror, although the science fictional elements are considerably downplayed, appearing in the form of new species of existing creatures. This was a common theme of Hodgson’s and appeared in such stories as “The Mystery of the Derelict” (1907), “The Terror of the Water Tank” (1907), “The Voice in the Night” (1907), and “The Stone Ship” (1914) among others.

On occasion, Hodgson needed no science fictional element at all. In “The Shamraken Homeward-Bounder” (1908), a ship of aged sailors, returning from its final voyage, encounters a strange pink mist. A sense of awe is built up as the ship is enshrouded in “great rosy wreaths (which) soften and beautify every spar.” The men believe they are about to enter heaven as the mist assumes an unearthly red brilliance and they see “a vast arch, formed of blazing red clouds.” A “prodigious umbel” appears, burning red and with a black crest, at which the men exclaim, “The Throne of God!” What the men have actually seen is “the Fiery Tempest,” a rare electrical phenomenon preceding certain types of cyclone. The umbel was the beginning of the water spout. As the story closes, “the breath of the cyclone was in their throats, and the Shamraken . . . passed in through the everlasting portals.” Using the theme of Man against the mysterious forces of Nature, Hodgson has created a vision of awe and supernatural dread.

Similarly, in “Out of the Storm,” an intense aura of fear and horror permeates the narrative of the last survivor aboard a wrecked and sinking ship. The sea itself, referred to by the man as “the Thing,” seems to take on an evil sentience as it closes in. The horror of destruction by immense, impersonal forces was later to become a major theme of Lovecraft’s.

More typically, however, Hodgson’s fiction includes a bizarre fantastic element. In his first published novel, The Boats of the Glen Carrig” (1907), the survivors of a shipwreck come upon a strange barren land populated by grotesque plant life and a creature having the appearance of “a many-flapped thing shaped as it might be, out of raw beef but … alive,” among other horrors. Later in the novel, after leaving this place, the men encounter a weed-choked expanse of sea and are attacked by quasi-human “weed men.” These creatures have short stumpy limbs, the ends of which are divided into “wriggling masses of small tentacles.” They have great eyes, “so big as crown pieces,” and bills like an inverted parrot’s bill.

These creatures are somewhat reminiscent of such Lovecraftian creations as Dagon and Cthulhu, both of which combined humanoid and aquatic features. It is certain, however, that Lovecraft wrote the stories in question before he became aware of Hodgson’s fiction. He independently created a similar literary device, a decade later, to evoke a similar mood of horror.

Hodgson’s second published novel, The House on the Borderland (1908), is a great leap forward. Where Boats merely deals with strange and unexplored regions of Earth, House transcends time and space.

The House on the Borderland tells of an old man living in a strange and isolated old house in Ireland and of the dislocations in time and space he is subjected to. On one occasion, after seeing a vision of a vast reddish plain while seated in his study, he finds himself floating upward through the night into limitless space. He eventually descends to the plain of his vision, and finds a replica of his house, although it is larger and colored green, at the center of a huge natural amphitheatre. Peering down at the house from the encircling mountains are great likenesses of the Egyptian god Seth, the Destroyer of Souls; Kali, the Hindu goddess of death, and other “Beast-gods, and Horrors” in vast numbers. At first he assumes them to be sculptures, but soon realizes “. . . there was about them an indescribable sort of dumb vitality that suggested . . .a state of life-in-death . . . an inhuman form of existence that well might be likened to a deathless trance — a condition in which it was possible to imagine their continuing, eternally.” (p. 25, Ace edition). Again, this is remarkably reminiscent of Lovecraft, particularly the couplet in “Call of Cthulhu” which goes “That is not dead which can eternal lie, / And with strange eons even death may die,” referring to the Great Old Ones in their stone houses in R’lyeh.

Returning to Hodgson’s novel, the narrator is again transported through space, and returns to Earth, to his study, and notes that 24 hours have passed. In later sequences, he is transported to an eerie gray world where he meets a beautiful woman by the shore of an “immense and silent sea,” and travels through time to witness the end of the solar system. In the latter, time speeds up as the narrator sits in his study. The hands of his clock begin to race around, and night and day alternate in more and more rapid succession. His dog dies and disintegrates as he watches, but he continues as a wraith-like presence to observe the sun die and travel to a huge double sun at the center of the universe. This central sun is composed of a green star, which the narrator feels houses some sort of intelligence, and a dead black star. The green one is surrounded by shimmering globules, one of which he enters, only to find himself again in the gray world with his love by the shore. When the green sun is eclipsed by the black one, he finds himself surrounded by ruddy spheres. He enters one and is transported back to the amphitheatre on the red plain. When he goes into the enlarged green replica of his house, there is a loud screaming noise, a “blurred vista of visions,” and he is suddenly back in the present. Nothing has changed, except for the crumbled remains of his dog lying at his feet.

Another bizarre touch in the novel is the presence of quasi-human swine creatures, which exist both on the red plain, and in a pit beneath the house on Earth. They are possessed of a malign intelligence, and after battling the narrator throughout the book, eventually destroy him.

Despite the diversity of the plot elements, and their somewhat episodic nature, they all seem to tie together with a strange sort of logic. More importantly, although Hodgson’s universe is somewhat more orderly than Lovecraft’s, this novel succeeds admirably in attaching the emotion of fear to the vastness of the cosmos. It is possible it may have been influential on some of Lovecraft’s later works.

Hodgson’s third published novel, The Ghost Pirates (1909), explores yet another direction, that of the parallel universe. It concerns a haunted ship plagued by one unexplained occurrence after another in an ever-increasing atmosphere of fear and horror. But the haunting is not caused by ghosts in the conventional sense. The narrator explains: “I’m not going to say they are flesh and blood; though at the same time, I’m not going to say they’re ghosts… this ship is open … exposed, unprotected [due, perhaps, to “magnetic stress” ] … the things of the material world are barred, as it were, from the immaterial; but … in some cases the barrier may be broken down. [The shipl may be naked to the attacks of beings belonging to some other state of existence. Suppose the earth were inhabited by two kinds of life. We’re one and they’re the other. They may be just as real and material to them as we are to us.”**

This idea of a barrier, protecting us from malign entities from Outside, is central to the mythos which ties together many of his later stories, and is reminiscent of Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos, particularly in such stories as “The Dunwich Horror.”

In later sequences of The Ghost Pirates, passing ships seem to appear and disappear as the haunted ship, and its crew, hover between the two planes of existence. The third mate on another passing ship notes at the end of the novel that the haunted ship was totally silent; he could see the captain shout, but no sound came from his lips. Later, he and his fellow crewmen hear sounds begin to come from the ship,”…very queer at first and rather like a phonograph makes when it’s getting up speed. Then the sounds came properly from her and we heard them shouting and yelling.” In all, it is an extremely effective portrayal of horror lurking just beyond our plane of reality.

Hodgson’s mythos achieves its fullest development in Carnacki the Ghost-Finder (1910), a collection of stories about one of the earliest psychic detectives. Carnacki often refers to, in the course of his investigations, a volume called the Sigsand MS. This book, or manuscript, is supposed to have been written about the 14th century. Quotations from it, scattered throughout the stories, indicate that it is concerned with “Monsters of the Outer World,” and defenses against them. In other words, it is very much like the Necronomicon.

Using information from the Sigsand MS., Carnacki develops a defensive circle containing a pentacle and certain “signs of the Saaamaaa Ritual.” Within this chalk circle he places an electric pentacle, suggested by another fictitious book, Prof. Garder’s Experiments With a Medium. While standing within these defensive barriers, a person is protected from various “powers of the Unknown World,” such as the “Outer Monstrosities” and the “Aeiirii forms of semi-materialization.” The defense is not good against “Saiitii phenomena,” however, since these can “reproduce (themselves) in or take to (their) purposes the very protective material you may use.” They involve “the very structure of the aether-fibre itself,” we are told in the story “The Whistling Room.” In the same story we learn that he Unknown Last Line of the Saaamaaa Ritual,” used by the “Ab-human priests in the Incantation of the Raaaee,” may be uttered by the inscrutable Protective forces which “govern the spinning of the outer circle and intervene between the human and the Outer Monstrosities.”

In the story “The Searcher of the End House” we are told that certain of the Monstrosities of the Outer Circle are known as “The Haggs,” and, according to the Sigsand MS., they cause children to be still-born by snatching back their ego or spirit.

Possibly, the most important story in the group is “The Hog,” which, for some reason, was never published during Hodgson’s lifetime, and did not see print until the 1940’s. It concerns a man whose natural insulation against the Outer Monstrosities breaks down. His soul is attacked by one of the Monstrosities known as the “Hog.” A quotation from the Sigsand MS. tells us “…in ye earlier life upon the world did the Hogge have power, and shall again in ye end. And in that ye Hogge had once a power upon ye earth, so doth he crave sore to come again” (Panther edition, p. 188). Unless the manuscript of this story was tampered with by August Derleth, who released it for publication, this passage is one of the most remarkable literary coincidences of all time, since it is a paraphrasing of the quotation from the Necronomicon in “The Dunwich Horror” which runs “…the Old Ones broke through of old and… They shall break through again… Man now rules where They ruled once; They shall soon rule where man rules now.”

At the end of “The Hog” is a lengthy explanation of the Outer Monstrosities. The Earth is surrounded by an Outer Circle 100 thousand miles up and 5-10 million miles in thickness, which spins opposite to Earth’s rotation, and consists of extremely rarefied matter. Out of it breed the Outer Monstrosities, which are million mile clouds of force, in the same way that sharks are bred out of the ocean. These monsters chiefly desire the psychic entity of man.

In short, the Carnacki stories are based on scientifically rationalized beings from beyond, causing apparently supernatural phenomena. The Hog from the above story may be a retroactive attempt to include the swine creatures from The House on the Borderland in the developing mythos; the descriptions are similar. Another Carnacki story unpublished during Hodgson’s lifetime, “The Haunted Jarvee,” contains much of the theory presented in The Ghost Pirates and appears to be a reworking of the same material in a shorter form.

It is interesting to compare the Carnacki stories to their immediate predecessor, John Silence —Physician Extraordinaire (1908) by Algernon Blackwood. John Silence is also a psychic detective, but in the five stories in the book, he deals with such stock occult menaces as a fire elemental, a werewolf, and persistant spirits of witches who turn themselves into cats. Most of the stories deal with the persistence of evil thoughts after the death of their perpetrators.

Silence combats them with the power of his own mind, rather than the “scientific” methods of Carnacki.

Hodgson’s final novel to be published and his most ambitious appeared in 1912. The Night Land is a minor classic, both of horror and of science fiction. The setting, this time, is Earth in the far, far future. Not only has the sun burned out, but millions of years have passed since. Mankind’s last refuge is an eight mile high metal pyramid built in a deep chasm, 100 miles below the Earth’s frozen surface. Surrounding the pyramid are strange monstrous creatures, which lie in wait through the ages, until power for the pyramid’s defenses runs out. The monsters are explained in this passage: “… olden sciences … disturbing the unmeasurable Outward Powers, had allowed to pass the Barrier of this Life some of those Monsters and Ab-human creatures, which are so wondrously cushioned from us at this normal present. And thus there materialized, and in other cases developed, grotesque and horrible creatures… And where there was no power to take on material form, there had been allowed to certain dreadful forces to have power to affect the life of the human spirit.” (Ballantine edition, Vol I, p. 32). This is obviously a continuation of the mythos in the Carnacki stories. Further, the pyramid is protected from these creatures by a “great circle of light” which “burned within a transparent tube,” and is called the “Electric Circle.” In other words, an enlarged version of Carnacki’s electric pentacle. It should be noted that despite the supernatural overtones of the passage, particularly at the end, it is scientific meddling which has resulted in the presence of the creatures.

In “Eloi Eloi Lama Sabachthani” (1912), the mythos reappears. In this story, Hodgson attempts to rationalize scientifically an occurrence described in the Bible: the darkness that appeared during the crucifixion of Christ. The result is an extremely effective horror story. A scientist synthesizes a substance which, when oxidized, disturbs the ether, interfering with the transmission of light. He ingests the substance, and drives nails through his palms to simulate the agony of Christ. Darkness forms around him. But something goes wrong. The scientist goes deeper and deeper into a trance-like state, losing awareness of his surroundings. Suddenly, he yells out the words, “Eloi, Eloi lama sabachthani!” (My God, My God, why have you forsaken me), first in terror, then in a voice not his own, but “sneering in an incredible, bestial, monstrous fashion.” A moment later he is dead. The narrator, who has been observing the scientist, suggests, “in his extraordinary, self-hypnotized, defenseless condition, he was ‘entered’ by some Christ-apeing Monster of the Void.”

Hodgson’s best short story was perhaps “The Derelict,” also written in 1912. A ship comes across a derelict at sea, and the crew row out to investigate. They find it to be surrounded by a thick scum and covered with a thick gray-white mold that is streaked with purplish veins. There is a persistent thudding sound aboard, and when the Captain kicks a hole in one of the white mounds of mold on deck, a purple fluid spurts out in time to the thudding. Terror mounts as the men realize that the entire ship is covered by a single living organism, and they barely escape being sucked into the thing and digested. But as in the previous story, this goes beyond a mere science fiction horror story. It is set in a framework in which a doctor, who was one of the crew, tells the story as an example of his theory that Life force will manifest itself if given the proper material and conditions. He goes on to say that Life, like Fire and Electricity is of the “Outer Forces – Monsters of the Void.”

As I hope I have demonstrated here, Hodgson was a real pioneer. He used the emerging scientific picture of our universe in a consistent manner to create a new type of horror story, a type which Lovecraft later, and independently, developed more fully.

He was the first literary Copernicus.

*August Derleth, ed.. Something About Cats (Arkham House, 1949) Darrcll Schweitzer, ed., Essays Lovecraftian (T-K Graphics, 1976), p.6

**Sam Moskowitz, ed., Horrors Unseen (Berkley ’74), pp. 51-2

—————————————–

This article first appeared in Nyctalops January, 1980.